Your intellect is in fragments, like bits of gold

scattered over many matters. You must scrape them

together, so the royal stamp can be pressed into you.

Cohere, and you'll be as lovely as Samarcand

with its central market, or Damascus. Grain by grain,

collect the parts. You'll be more magnificent

than a flat coin. You'll be a cup

with carvings of the king

around the outside

— Rumi, Masnavi IV 3290-3294 - Translated by Coleman Barks

Introduction

I have already written about Dostoevsky’s The Brothers Karamazov twice before in the posts below so I was hesitant to revisit his work again for our topic today in order not to exhaust my readers' patience.

But having seen

make a whole Substack on a single novel (Tolstoy’s War & Peace) and a single series (Mantel’s Cromwell Trilogy), I was encouraged to revisit Dostoevsky's work once more.In general, as I’m growing older, I am seeing myself becoming more interested in revisiting books I have already read rather than dedicating time to reading new books.

In this, I seem to be converging to the same view as Naval Ravikant:

‘I don’t want to read everything. I just want to read the 100 great books over and over again.’ I think there’s a lot to that idea. It’s really more about identifying the great books for you because different books speak to different people. Then, you can really absorb those.

— Naval Ravikant

Extracting value over the long term from our books is maybe a topic for another day, but I could not stop myself from returning to Dostoevsky’s novel for the topics that were on my mind for a while now.

How do we know what we are missing? How can we find it? And how can we integrate it with us to make ourselves whole?

The Brothers Karamazov - a race against time

[...] The 'kingdom of Heaven' is a condition of the heart - not something that comes 'upon the earth' or 'after death'. [...] The 'kingdom of God' is not something one waits for; it has no yesterday or tomorrow, it does not come

'in a thousand years' - it is an experience within a heart; it is everywhere, it is nowhere...

— Friedrich Nietzsche, The Anti-Christ (34)

Dostoevsky’s novel The Brothers Karamazov, set over approximately four days, can be seen as a race between the Karamazov brothers to integrate different parts of their personalities.

Their passions compel them to act in their own interests. Their intelligence which allows them to pierce through the traditions and structures of society. And their imagination which allows them to believe in the absurd idea of God in a world full of suffering.

Each brother starts the novel possessing one of the three aspects and must not only recognize the part he is missing but also find it and integrate it with his persona.

The stakes are high as each brother faces a race against time to resolve their internal crises in the wake of their father’s murder and against the backdrop of nineteenth-century Russia, an era rife with societal upheaval and spiritual change.

The price of failure is literally self-destruction — being torn apart by the contradictions within one's own psyche and the tensions of the external world.

Dmitri, the eldest, an ex-military man, starts as the sensualist, a man driven by his passions, living in the moment; engaged in womanizing, infidelities and debauched revelries. Neither possessing the intelligence to control his passions for the benefit of others nor the imagination to believe in anything beyond his self-interest, Dmitri is seen languishing in prison towards the end of the novel ready to be shipped to a Gulag

Ivan, the middle brother, is a brilliant intellectual who sees through the lies and hypocrisies of society. However, lacking the passion to act on his convictions and the imagination to believe in anything beyond the dark and meaningless world his reason shows him, he descends into madness

Alyosha, the youngest brother, turns out as the winner in this race. He starts the novel as a novice monk who possesses deep imagination and faith, allowing him to see the good in everyone around him but lacks the passions to act on his convictions and the intelligence to understand the complexities of the world.

As the novel progresses, Alyosha undergoes significant personal growth through his interactions with various characters. His relationship with his "girlfriend" Lise, as well as his encounters with the seductive Grushenka and the dignified but conflicted Katerina Ivanovna, help him access, develop and govern his sensual side.

Moreover, through his intellectual debates with his older brother Ivan, Alyosha comes to recognize the importance of reasoning and logic. He realizes that to influence others and command their respect, he must be able to articulate his thoughts and beliefs clearly and persuasively.

By the end of the novel, we see Alyosha leaving the Monastery, an environment which only engaged his imaginative side, to enter the world as a man of affairs, equipped not only with a strong sense of belief in the good of humanity, but also a sharp intellect to navigate the complexities of society, and as well a newfound ability to harness his passions for his own good and for the good of those around him.

The novel concludes with a poignant scene where Alyosha delivers a heartfelt sermon to a group of young boys gathered for the funeral of their cherished friend.

The same group of boys who once scorned him for his perceived naivety now find themselves captivated by his words and cannot help but regard him with newfound respect.

Alyosha's journey has transformed him into a man of wisdom, intelligence and compassion, earning him the admiration of even his harshest critics.

The Power of the Intellect to foster our Self-delusions

Above all, do not lie to yourself. A man who lies to himself and listens to his own lie comes to a point where he does not discern any truth either in himself or anywhere around him, and thus falls into disrespect towards himself and others.

— Dostoevsky - Father Zosima in The Brothers Karamazov

Before we go on to focus on Alyosha’s success, I believe that the more compelling question to ask is why Dmitri and Ivan fail where Alyosha succeeds?

Ivan’s failure is particularly interesting given his rational, methodical, and scientific mind which should have, technically,allowed him to see his misgivings most clearly and fix them.

Ivan is all the more interesting, because he is, in fact, the embodiment of the modern man of the twenty-first century. A man who believes in science, intellect, logic and using them to improve himself.

But that is not what happens.

And the answer as to why he fails can be found right at the beginning of the novel, in a scene where his brothers and his father have gathered in front of the Christlike elder monk Father Zosima, known for his wisdom and insight, to resolve a dispute over their inheritance.

In this scene, Ivan, who has recently written an article attacking the church, delivers a powerful speech, revealing his deep-seated doubts about the existence of God and the immortality of the soul.

He argues that, with the declining faith in God as a result of modernity, and without the promise of eternal life, morality becomes meaningless, and people are free to act as they please without consequence.

Father Zosima, however, sees through Ivan's intellectual facade resulting in the exchange below (character names added by author for clarity):

Zosima: ”Can it be that you really hold this conviction about the consequences of the exhaustion of men's faith in the immortality of their souls?" the elder suddenly asked Ivan Fyodorovich.

Ivan: ”Yes, it was my contention. There is no virtue if there is no immortality."

Zosima: ”You are blessed if you believe so, or else most unhappy!"

Ivan: ”Why unhappy?" Ivan Fyodorovich smiled.

Zosima: "Because in all likelihood you yourself do not believe either in the immortality of your soul or even in what you have written about the Church and the Church question."

Ivan: "Maybe you're right ... ! But still, I wasn't quite joking either …," Ivan Fyodorovich suddenly and strangely confessed—by the way, with a quick blush.

Zosima realizes the power of Ivan’s intellect and continues:

Zosima: "You weren't quite joking, that is true. This idea is not yet resolved in your heart and torments it. But a tormented person, too, sometimes likes to toy with his despair, also from despair, as it were. For the time being you, too, are toying, out of despair, with your magazine articles and drawing-room discussions, without believing in your own dialectics and smirking at them with your heart aching inside you ... The question is not resolved in you, and there lies your great grief, for it urgently demands resolution ..."

Ivan: "But can it be resolved in myself? Resolved in a positive way?" Ivan Fyodorovich continued asking strangely, still looking at the elder with a sort of inexplicable smile.

Zosima: "Even if it cannot be resolved in a positive way, it will never be resolved in the negative way either—you yourself know this property of your heart, and there lies the whole of its torment."

Zosima: But thank the Creator that he has given you a lofty heart, capable of being tormented by such a torment, 'to set your mind on things that are above, for our true homeland is in heaven'! May God grant that your heart's decision overtake you still on earth, and may God bless your path!"

The scene concludes with an exchange of mutual respect between the two:

The elder raised his hand and was about to give his blessing to Ivan Fyodorovich from where he sat. But the latter [Ivan] suddenly rose from his chair, went over to him, received his blessing, and, having kissed his hand, returned silently to his place.

He looked firm and serious. This action, as well as the whole preceding conversation with the elder, so unexpected from Ivan Fyodorovich, somehow struck everyone with its mysteriousness and even a certain solemnity, so that for a moment they all fell silent, and Alyosha looked almost frightened.

This scene marks the only interaction between Ivan and the saintly Zosima, who is possibly the sole character in the novel to grasp no only the profound depth of Ivan's self-delusions but also the lack of imagination that can help him transcend them.

Man is very well defended against himself, against his own spying and sieges; usually he is able to make out no more of himself than his outer fortifications. The actual strong-hold is inaccessible to him, even invisible, unless friends and enemies turn traitor and lead him there by a secret path.

— Friedrich Nietzsche, Human, All too Human (491)

Both Zosima and Ivan recognize that Ivan is his own worst enemy.

They realize that Ivan's intellect is too sharp for his own good, as it will relentlessly scrutinize and dismantle every belief that crosses its path, offering him no respite from the questions that torment him.

They both realize that Ivan is only capable of using his intellect as a tool to destroy beliefs, and cannot access his imaginative side to build anything on top of the rubble

And in this shared understanding of Ivan's ultimate fate, the saint and the disbeliever share a fleeting moment of kinship, confounding everyone present in the room.

The Power of Imagination to free us

From experience - That something is irrational is no argument against its existence, but rather a condition for it.

— Friedrich Nietzsche, Human, All too Human (515)

It is ironic that Ivan, the brother endowed with the sharpest intellect among the three, finds himself ensnared by delusions that lead him inexorably toward madness.

Why is it that Ivan unable to surmount his self-deceptions?

The answer to Ivan’s failure and Alyosha’s success lies in overcoming their self-delusions lies in their lack-of and possession-of imagination, respectively.

While Ivan's intellect is unparalleled, he lacks the imaginative capacity to transcend his rational arguments embrace a higher purpose. Alyosha, on the other hand, possesses a powerful imagination that allows him to see beyond the confines of logic and reason to believe in God despite the irrationality.

While Ivan possesses the intellect to see the wretchedness of mankind, Alyosha possesses the imagination to believe in the fundamental goodness of everyone he meets despite all the evidence of debauchery, treachery, and cruelty they give him.

Ivan has the intellect to gaze at the abyss but not the imagination to look away from it.

“Whoever fights monsters should see to it that in the process he does not become a monster. And if you gaze long enough into an abyss, the abyss will gaze back into you.”

―Friedrich Nietzsche, Beyond Good and Evil (146)

Ivan’s intellect isolates him from others; Alyosha’s imagination unites him.

Dostoevsky’s message, in The Brothers Karamazov, and other works such as Notes from Underground, Crime and Punishment, and Demons is not that we cannot survive without God but rather that we need imagination if we are to survive in the wake of the “Death of God.”

As I wrote in my post previously: Why am I on Substack? “This is what Nietzsche meant when he said ‘We have Art in order not to die of the Truth.’ This is why Rumi wrote odes and odes to love. This is what Dostoevsky meant when he said ‘Beauty will save the World.’”

Nietzsche, Rumi, Dostoevsky - they are trying to tell us not to give up our imagination, lest we want to risk losing our humanness.

They are all trying to tell us that without the power of imagination we can never hope to get over our delusions, to truly understand ourselves, to identify what is missing and to integrate it to become whole.

They are all trying to tell us that without imagination there cannot be any self-discovery.

Conclusion

“If you want your children to be intelligent, read them fairy tales. If you want them to be more intelligent, read them more fairy tales.”

— Albert Einstein

The success of a man has always been determined by his ability to integrate his disparate parts - his passions, his intellect and his imagination.

But it is his imagination that is necessary to ignite and guide the other two. It is the cornerstone upon which the integration of the self rests — without imagination, passions have no direction and the intellect has no purpose

That is the message Dostoevsky, Nietzsche, Rumi, Einstein, and countless others poets, philosophers, playwrights, artists, writers, novelists, scientists and psychologists.

Belief in God, belief in anything really, is built on a strong sense of imagination. A sense of imagination which compels us to take the leap of faith towards ideas and ideals that are not visible or immediately rational.

It seems that, having stopped ‘believing’ in God we have lost the ability to believe in anything at all.

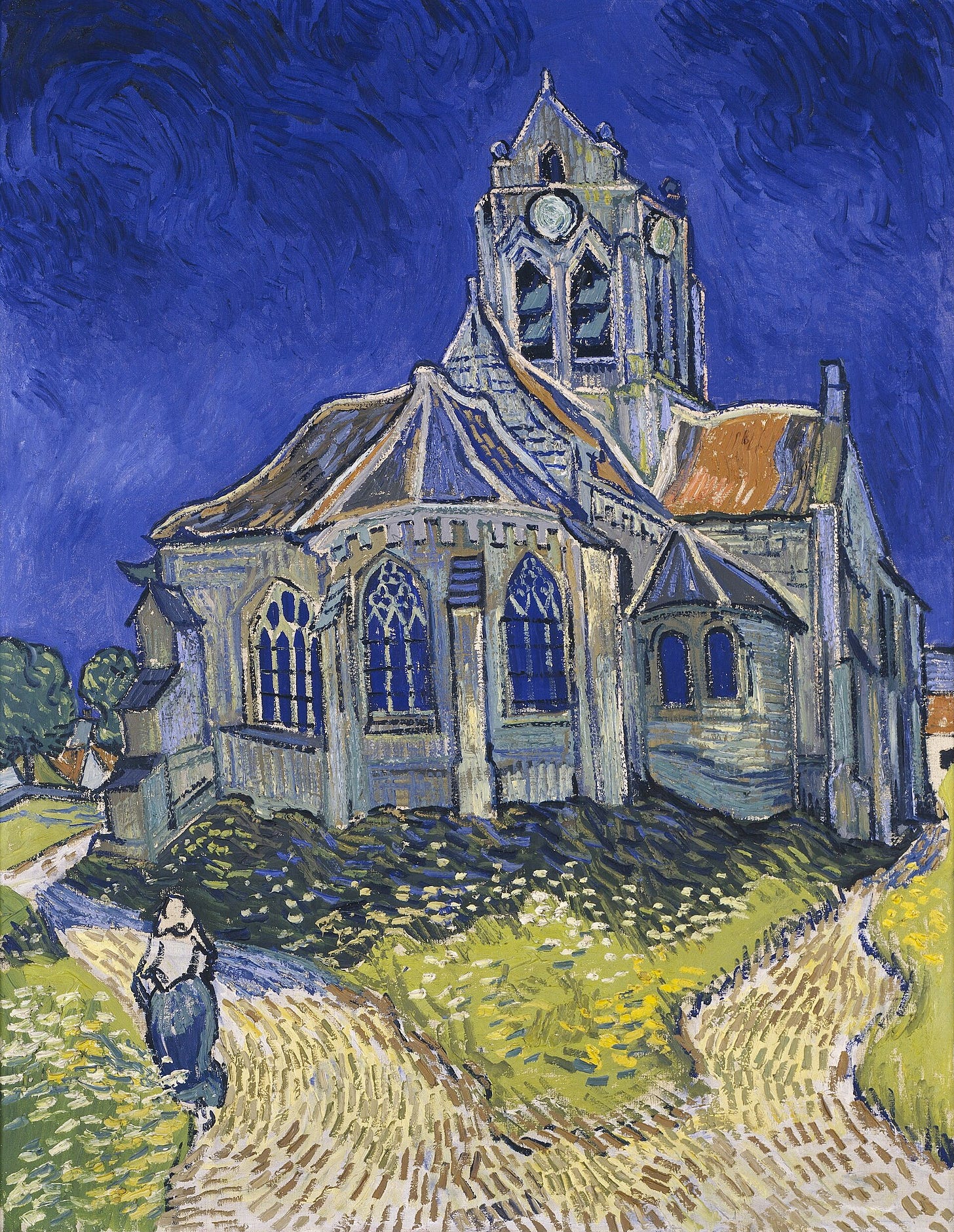

People seem to be decrying the death of imagination in everything around us — Death of imagination in Literature; death of imagination in Architecture; death of imagination in Culture. The list is endless.

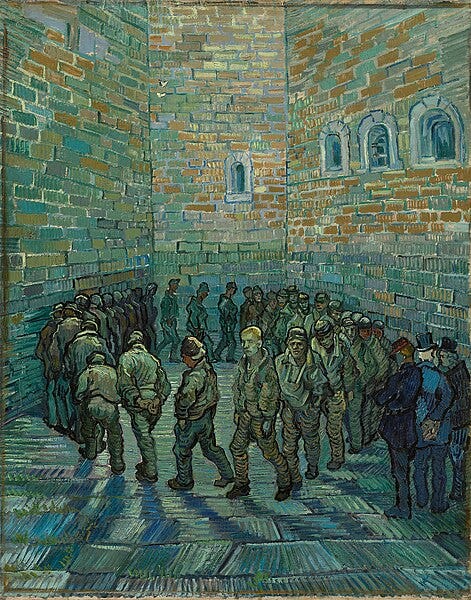

It seems that imagination, just like everything else in life, is a muscle — you stop using it and it atrophies; and before you know it, it is gone leaving you stuck in the prison of your knowledge built by your intellect.

We have lost the ability to imagine anything else other than that which is immediately in front of us or that which comes to us immediately after — anything longer than that requires powers of imagination which we no longer possess.

Further Explorations

It is worth considering that most, if not all, of the world’s sacred books are first and foremost works of literature that use stories, parables, and metaphors to convey profound truths about the human condition.

What is more is that, most, if not all, have an element of the poetic in their original languages. Examples include the the Rig Veda, the Upanishads, the Mahabharata in Sanskrit; the Tao Te Ching in Classical Chinese; the Dhammapada in Pali; the Tanakh in Hebrew; and the Koran in Classical Arabic.

Through the use of literary devices these works not only engaged our intellect but nurtured our imagination.

They understand that without rousing our imagination, they cannot free us from our intellect which keeps us trapped in The Curse of Knowledge.

But in a world that has lost its belief in God and the ability to understand the original languages of most of these sacred poetic texts, we have no other option left but to cultivate our imagination through other means.

Before I sign-off, I would like to share some of my reading on Substack, related directly or indirectly, to imagination — the importance of it, the magic that can happen when we possess it, and the dangers that await us when we don’t.

shares a lovely short poem on the importance of imagination in our life. explores the concept of wonder as a place where emotional and intellectual powers converge. argues that our modern culture of ease, over-saturation, and explicitness is undermining our imagination and humanity. critiques the dominance of rationalistic thinking in the modern world, arguing that it has led to an impoverished experience of life without wonder. talks about the radicalism in universities. But really, what he is talking about, is a lack of our imagination to believe in that which is common to all of us — or anything else for that matter. and , in articles I shared previously, write about the implications of a world increasingly devoid of imagination. We end up playing short term games dictated by others. shares how his ability to imagine a different future allowed him to make progress on his path to self-discovery.I hope these diverse perspectives inspire you to nurture and protect your own imagination as an essential tool for growth, meaning and finding wholeness.

If you enjoyed this post, I would love if you would consider sharing the post to help support my writing on this platform.

If you are new here and want to receive updates in the future then feel free to subscribe using the button below.

I would love to hear what you think about the importance of imagination in our lives. What have been your observations about the role of imagination in your own life? Has it helped or hindered your personal growth and self-discovery?

In the meantime I’d like to leave you with this lovely and thought provoking poem from Rumi which I shared previously, but cannot stop reading:

“If you quit thinking for one hour,

what will happen?

If you plunge like a fish into Love's ocean,

what will happen?

—

When worries keep you up at night,

picture the seven sleepers

slumbering in a cave for centuries, resting in faith.

You'll be filled with holy light

no matter where you lay your head.

—

Straw man,

at the end of your straw world,

there's a fragrant field of amber.

If you leap from your high haystack and join us,

what new heights will you reach?

—

Again and again, you vowed to be humble as soil.

You broke your word every time.

When you keep it, what will bloom?

—

You are a gem covered in mud and clay.

Your beautiful face is hidden.

—

You came down from the heavens.

The high angel adores you and still,

you feel like a poor wretch.

If you remember who you are,

What will you become?

—

You seek truth but you don't trust

a single truth teller. I know a true seer.

Listen to him. See what happens.

—

A fragment, a hand longing for its body,

you dream of greatness,

grandiose fantasies,

gripped by greed, gripped by pride.

—

Give yourself up.

Give yourself over to glory.

See what happens.

—

You are a mountain full of gold.

Open the mine. Let the mountain speak.

Hear what happens.”

- Ghazal #844 - Translated by Haleh Liza Gafori

The Brothers Karamazov is such an inexhaustible book. I don't think I could ever get tired of reading it or reading about it.

And I love how much additional content you link in your posts, it makes each one feel like a treasure trove that opens up lots of other little doors!